Laura Lee Bennett reviews Carolyne Wright's Masquerade: A Memoir in Poetry

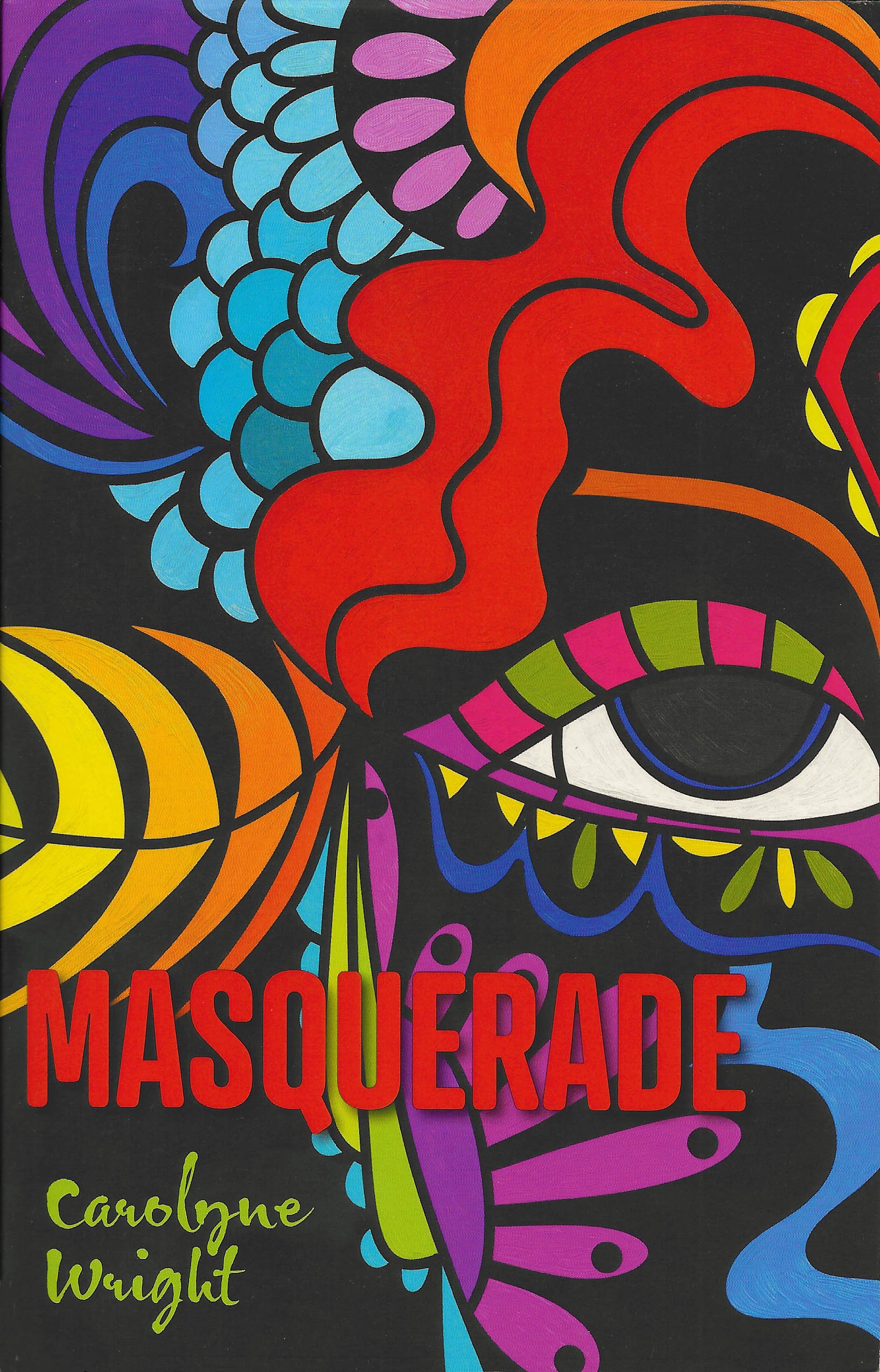

MASQUERADE: A Memoir in Poetry

A review by Laura Lee Bennett

Carolyne Wright is a force of nature in these parts. Celebrated poet, essayist, “scholar gipsy,” teacher, editor, translator, and reader, she has traversed continents, cultures, and political landscapes. She has provided closely held, intuitive renderings of poets' struggles in other lands (Seasons of Mangoes and Brainfire, 2005). Among many other posts, she is on faculty at Seattle’s Richard Hugo House, and from 2005–2016 she taught at the Northwest Institute of Literary Arts’ Whidbey Writers Workshop MFA Program. Recently she taught a class, "Taking a Stand: Poetry and Prose as Peace March," using the Raven Chronicles anthology Take a Stand: Art Against Hate as a guide.

With Masquerade: A Memoir in Poetry, we have a gift of the poet at the peak of her powers looking back on her youth, incorporating the carnival culture of Mardi Gras and the jazz scene of New Orleans with her observations of local characters—the roller-skating, wedding veil-wearing Ruthie the Duck Lady, for example, “tough as a folded bird” in “Endecasyllabics: About the Women (Ruthie)”—as well as visits to her home state and the placid white culture there. She shares the story of a lost love with all the attendant sighs and confessions and pheromones.

We have the poet seeking home in both worlds—the order of poetic forms, and the swaying, ecstatic "confessions" of memoir—which by nature is prose. It is a lyric narrative—many of the poems have to do with music—and every poem carries fond references to jazz and the blues (indigo, cerulean, blue, and blues).

What struck this reader immediately was the “young” poet’s grasp of sensory detail, the depth of her self-awareness, and her metaphoric dance with the “handsome neighbor” to her writing studio. How she knew (and yet did not know) that she was nodding fatefully, giving in to desire—a lover of a different color, who opened the gates, who held secrets, who was not necessarily monogamous, after all. At first, she (ah, youth) spends much time wondering what will happen. Even as time passes—events transpire, and the poet later moves on to conflict, betrayals, and acknowledgment of loss—we bear witness to that thrall, that music, the smokey bar, the moans and trills of the blues and jazz.

We have the poet seeking home in both worlds—the order of poetic forms, and the swaying, ecstatic “confessions”

of memoir

From the start, we have experiential pangs of that early desire, as yet unfulfilled, with attendant literary allusion. In “At First Sight,” the poet writes of “Kismet’s / metabolic blow-dart,” but yet closes with a question / premonition: “Cupid’s curse / or Caliban’s cri – de – cœur?” In another poem of anticipation—and humor—“Watched by Whales,” she cites a young fin whale breaking from the pod, leaping straight up then sliding back down “like a pewter blade, shelving into / the wave-storm. I grip the rail / in a speechless breeze. I never / tell you—no man has ever thrust / his summer into me like that.”

One of the most telling poems is “Gumbo Nights,” from Part I, Cape Indigo. The poet encapsulates the headiness, the excitement, and foretells the ultimate melancholy of the affair. Against an uneasy backdrop, her tiny radio of Sarah Vaughn’s crooning Lover Man and Nina Simone’s “bent blue- / / violet notes,” and after a dinner of gumbo that “shimmers with scallops and okra, shallots and filé,” and the last of the “smoky and pale” chardonnay, the two would-be lovers appraise one another. It is still touch and go. He has just bid good-bye to another woman and a week-long rendezvous.

“Forget that foolish week,” you murmured—

your face, as I let you into my studio,

haggard with bravado. Did we know the midnight hour

had already tolled for us from the church steeple’s

pale melon clock face? Let's face the music

and dance, cried the music in my head,

ahead of yours for a change. A change going come,

I know, cried Sam Cooke, a change the woman

whose fury sent him out beyond the sky

never could have known. What did we know then,

as you stood up and came around my table

to take me again as your lover? Lover man, oh

where can you be? sobbed the jazz women

on the radio as the woman I was then

gave in and let you come, though I was already

moving away from the table.

There are other poems throughout the variegated, highly charged narrative that foretell the lovers’ doom by reactions of both of their families—in “White,” when her own mother advises, “‘You need someone just like him / but white.’” And in “Epithalamion in Blue,” the narrator observes, while visiting his family, “Who did we think we were? / Ebony Adam and ivory Eve”—and by the reactions of the denizens of the cities the couple inhabits. In Part 3, Crescent City, in the poem “The Divide: New Orleans,” the poet captures the character of “Miss Lucille Ann / Boudreau, Proprietress”—blue bouffant hair-do and all—with a few choice lines. “Hey honey! the lady behind the counter / chirps. How’s every little thang?”

Miss Lucille chatters on, and the poet realizes “the Olde South Gift Shoppe” is filled with antebellum hoopskirts and “An entire shelf / / of Mammy dolls.” Then the poet’s Black boyfriend enters—“figure obsidian / against the mullioned window,” smiling, pulling out books he has brought her, "Song of Solomon / and The Bluest Eye" (by activist and mythic novelist Toni Morrison). Suddenly the lavish attention from Miss Lucille turns negative: “Get up out that chair, / miss, less you mean to buy it.” The poet turns to leave the shop, her lover’s face a “Benin mask.” Together the lovers “step into the blistered street.”

The second half of the book recounts events that snap the poet to attention. In Part 6, Reflections in Blue, the poet stirs. She stands up. Finally accepting loss, and in “Sestina: That mouth . . .” she is “tired of living on the edge, / taking our losses up-front.” She also wonders, could they take one more season? The closing stanza of the last poem, "The Devil and the Angel," is plaintive, soulful:

. . . . I am the Angel

of No Losses, one wing in debt

divided, connected by the sun’s

infernal touchstone. Welcome

to my world. The demons are intrigued

by our hard choices.

Laura Lee Bennett received her MFA in creative writing from the University of Oregon in 1982. Soon after, she discovered Red Sky Poetry Theatre in Seattle. Today she actively supports written and spoken arts in her eastside community, including past service as president of the Redmond Association of Spokenword (RASP). She often emcees at RASP readings and open mic.

Recent contributions include poetry performances at “[R]evolution” (2015), an installation featuring five local artists/activists at Venues for Local Artists on the Eastside (VALA Eastside); poems for “Ekphrastic Assimilations” (2016), an interactive project bringing together visual artists and poets from China and the United States; and co-authoring a retelling of the Persephone myth, I Am Not Cursed (2016), with poets Elizabeth Carroll Hayden and Chi Chi Stewart. Currently she is working with her collaborators on publishing that manuscript as a chapbook.

In 2017, Laura had a chapbook published by nine muses books, Snake Medicine (First Step), drawn from a spoken word performance at Red Sky in the 1990s.

Masquerade: A Memoir in Poetry

Poems by Carolyne Wright

ISBN: 978-1-7364323-3-4

Lost Horse Press, Liberty Lake, WA

www.losthorsepress.org

2021, paperback, 168 pages, 5-1/2 x 8-1/2, $21 US