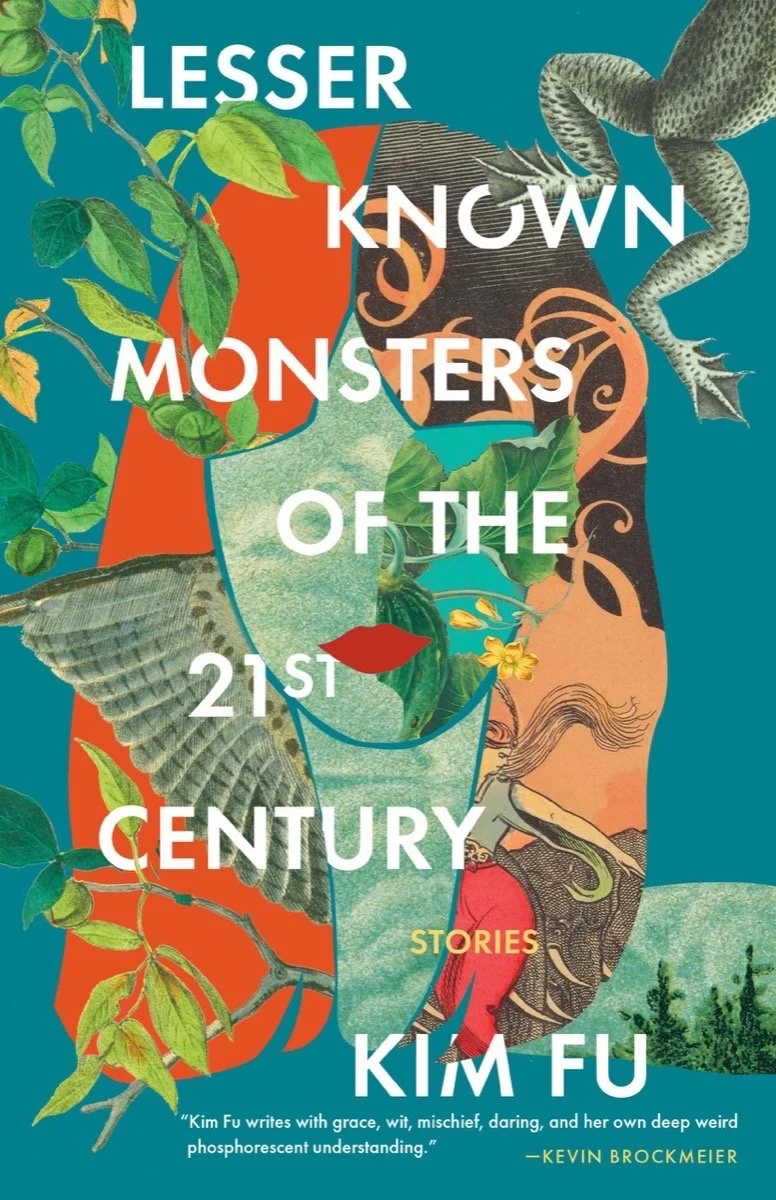

Nina Burokas Reviews "Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century" by Kim Fu

Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century

by Kim Fu

reviewed by Nina Burokas

In Lesser Known Monsters of the 21st Century, Kim Fu imagines worlds that are both familiar and fantastic, characters that are flawed, as all human beings are (monsters no exception) and examines the way we respond to life’s stresses. Days after finishing a story, the images still reverberate: Liddy standing, “her legs forming an inverted V…. The wings spread to a majestic span”; Miki veiling her intent in an oversized patterned scarf and exaggerated gestures; the surrealism of the Sandman; the mysterious smile on Connie’s face, “gone and back from somewhere I could never truly know, all her secrets her own, fascinating again”; and the experience of a classic French boule. These stories play out at the edges of our consciousness: not quite real and yet universal, relevant in proportion to one’s experience and imagination.

Fu is adept at capturing the gestalt of our times: boredom and wonder, the detachment and seduction of technology, a pervasive sense of grief/longing, the pressure to conform to some baseless, soulless norm, and the underlying threat of violence in a patriarchal society. For example, the narrator in “The Doll” identifies the point of friction as the neighbor’s non-conforming midcentury bungalow, ”the specific architectural dream of a designer or previous owner, representing a specific moment in time. Our houses were specifically for the dreamless, signifying nothing.” In “Liddy, First to Fly,” the young girls acceptance of their friend’s wings is clouded by foreknowledge: “Everything was baffling and secretive then, especially our own bodies, sprouting all kinds of outgrowths that were meant to be hidden…that could be weaponized against us.”

These twelve stories speak to our basic humanity: what is both human and inhuman in us. In “Liddy, First to Fly,” a group of young girls are initially repulsed and gradually become fascinated by a growth under the skin of Liddy’s ankles. Lanced, the growth reveals itself to be feathers, then wings—a physical projection of the girl's emerging sense of self. Grace, the narrator, muses “There was a way in which Liddy’s wings didn’t strike us as extraordinary. The realm of pretend had only just closed its doors to us, and light still leaked through around the edges.” Liddy continues to practice and test her wings, eventually moving to the Springboard, a rocky outcrop on a cliff overhanging the ocean, the scene of multiple deaths. As Liddy takes flight, the girls’ mothers arrive en masse and the narrator recognizes the trial flight is doomed: “If it had been one adult, the magic could have lasted.…”

The monster in “The Doll” is a toxic suburban mother who seems to exalt the misfortune of her neighbors, the Mullens, whose midcentury bungalow and carport was not “in keeping with the neighborhood,” a collection of two-story boxes with roofs that fit “as neatly as a lid to a jar,” as her son describes them. He goes on to note that “Though the Mullens kept it very neat, my mother had always found the carport obscene, sitting exposed among our garages….with their contents “kept hidden and out of sight as God intended.” The mother isn’t an outlier. As Matt, her son, observed in the aftermath: “The story occupied us all summer. The adults said how terrifying, what a tragedy, could have happened to anyone, their fear so false it sounded smug. Because it hadn’t happened to anyone. It had happened to the Mullens.”

A former climber, I gravitated to “#ClimbingNation.” This story, set at the memorial of a climber, Travis, is theater: the two leads—the dead climber’s sister, Miki, and his climbing buddy, Zach, the “magnetic poles,” as the narrator, April, observes. In his domain, Zach preens, shirt unbuttoned to reveal his chest hair, accepting condolences as his due and attributing Travis’ death to a mistake on his part. When another climber questions the chain of events, he balks. Even as it becomes clear that Zach caused Travis’ death, he is undaunted, oblivious that Miki is setting him up, fabricating a story of treasure as absurd as Zach’s story of the climbing accident. The ultimate seduction: an extreme mountaineering challenge with a fortune in gold at the end. #Karma.

Entering Kim Fu’s imagination is an experience both unsettling and satisfying….The most thought-provoking aspect for me is not a specific story or monster but the reflection, the mirror, Fu holds up for us.

The story I found most riveting—and disturbing—was “Twenty Hours,” starting with “After I killed my wife, I had twenty hours before her new body finished printing downstairs.” The narrator’s emotional flatline is replicated in the body collectors, who nod to the husband as they pick up her body—correction: her last printed body—for disposal. The husband refers to the murders as “a door to the world without our wives, to our larger selves beyond them,” and yet in those 20 hours he flounders. He imagines his neighbor saying “‘You want to kill your wife? Then get divorced.’ …. But…I want her to come back…boredom and disdain and resentment drained away as after a medieval bloodletting.” It’s a radical treatment for boredom.

In my Winter meditative mood, Fu’s stories prompted reflection on what makes life meaningful, the appropriate role for technology, and the impact it’s already had. In a The Harvard Gazette article titled “How death shapes life,” author Colleen Walsh quotes Susanna Siegel, Harvard’s Edgar Pierce Professor of Philosophy: “Both in politics and in everyday life, one of the worst things we could do is get used to death, treat it as unremarkable or as anything other than a loss.” [1] Would people be so angry, disengaged, or depressed if we weren’t so programmed for stimulation, so on the verge of being rendered obsolete by technology?

Entering Kim Fu’s imagination is an experience both unsettling and satisfying. It’s a bizarre combination that evokes the emotion felt when we hear a fortune or read a horoscope and consider whether the future is fated or made. The most thought-provoking aspect for me is not a specific story or monster but the reflection, the mirror, Fu holds up for us. I recently wrote a poem about being lost in the wilderness, my behavior that of a monster: so full of myself / so full of my need / to survive. These monsters aren’t among us; they are us. We are all monsters, all gods, all products of our own imagining.

Nina Burokas is a writer and educator working on the production of her first poetry chapbook. She lives on Washington’s Olympic Peninsula, where she’s restoring a woodland prairie on the traditional land of the Chemakum, Coast Salish, S'Klallam and Suquamish People. An adjunct business instructor at Mendocino College in California, Nina has been a contributing author/editor for five digital business titles.

"Lesser Known Monsters of

the 21st Century

by Kim Fu

ISBN: 978-1-951142-99-5 (Paperback)

Tin House

Publishers Website: https://tinhouse.com/

Link to Title: https://tinhouse.com/book/lesser-known-monsters-of-the-21st-century/

Tin House is distributed by W. W. Norton & Company, 500 Fifth Ave, New York, NY 10110; Tel: 212.354.5500

2022, paperback, 232 pages, $17.95