Jim Bodeen reviews Ann Spiers' & Bolinas Frank's "Rain Violent"

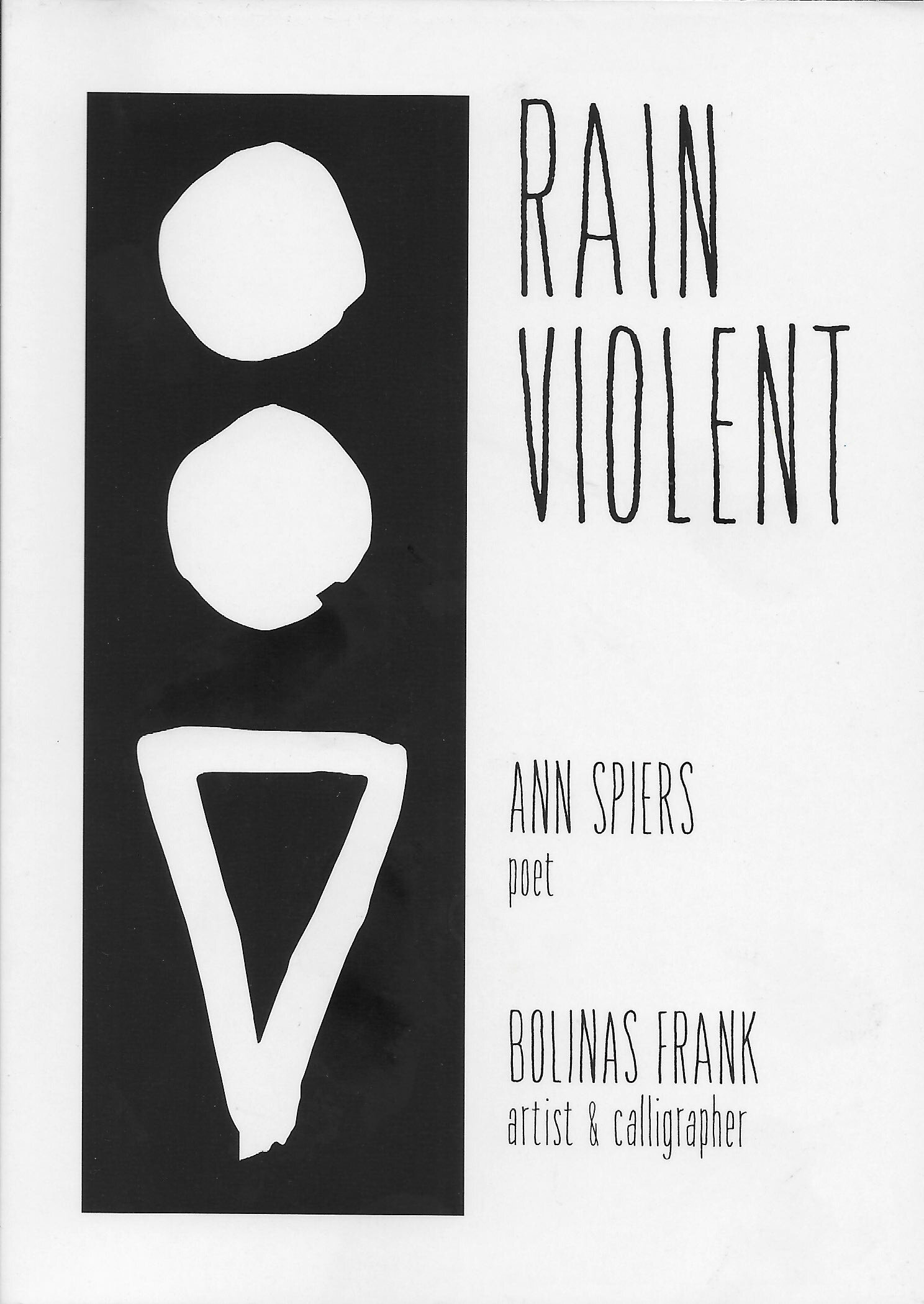

RAIN VIOLENT

Poems by Ann Spiers,

art & calligraphy by Bolinas Frank

ISBN; 978-1-7341873-9-7

Empty Bowl Press,

https://www.emptybowl.org

2021, paperback, 78 pages, 5 x 7, $16.00

WALKING OUT, WALKING INTO, RAIN VIOLENT

A review by Jim Bodeen

Over decades, the weather, poet Ann Spiers says, studying sky . . . “I became interested in daily local weather. We lived down trail in a beach cabin on fill bulwarked by a bulkhead with a green bluff behind. Daily weather mattered. The north wind arrives icy, gathering force as it rides the fetch south over the open waters of Puget Sound. That wind’s big waves ate our bulkhead, flooded our cabin.”

Daily weather inverted. Not violent rain, rain violent. What we’re in. Reading the poems, burning.

I pick a poem at random, “Drizzle Thick Freezing,” (pg. 12):

No berries, thus no bear rising

from the thicket, no awe at Ursa

circling the North Star. No Goldilocks

at my door with fattened bear stories.

Poetry’s ancestry woven tightly into the 4-line quatrains.

That’s it. The poem. Sixty-one poems like that. Go back to the title. “Drizzle Thick Freezing.” If you’re reading as a writer, ask yourself about your own titles. Say it out loud. The weather. How’s work? Your friends write. Start by telling you about the weather. About how they’re doing. You know how to proceed. And the language. The plosive b and d sounds. Berries, bear, gold, door, fattened, bear. “No” four times. This is not a recreational hike, no aha here for Ursa. Drizzle thick freezing. These poems help us interpret our lives. What the weather knows. Surprising quatrains. Weather on its way. It’s personal, the weather.

How does the reader change the weather? I ask artist Bolinas Frank.

“This is the most bizarre and interesting question,” Bolinas says. “The reader changes the weather by changing their perspective. Can they look at a cloud, and see it as an absence of sky? Or by reading into the observed phenomena? For example, the reader can try and look at a cloud, and see it as a shape that looks like a cat. I’ve been trained to never say can’t. Going further and practically speaking, the reader actually can change the weather.”

We’re in this weather together, reader. Weather coming at us, in the form of poems and a hand-painted typeface. Rain Violent by poet Ann Spiers and artist Bolinas Frank.

*

N. Scott Momaday (from the poem “The Delight Song of Tsoai-Talee”):

“I am the roaring of the rain.”

Lois Red Elk (from the poem “Our Blood Remembers”):

”The day the earth wept, a quiet wind covered the

lands weeping softly like an elderly woman, shawl

over bowed head. We all heard, remember? We were

all there . . .”

This is the weather report. A reading of Ann Spiers’ poems, Rain Violent.

Rain Violent gives you the signs of what’s coming. Signs of what’s here.

These are the rains from Star River.

This is the weather report, Ann Spiers, reporting. This is the report from Four Seasons, reporting from the I Ching, from the tossing of the coins. What yarrow sticks have to say.

Data clear. Dada clear. Data dearest.

Hozho beauty. Show me something that isn’t beautiful.

*

Ann Spiers: “That Empty Bowl published it, that publisher and poet Michael Daley and designer TonyaNamura realized Bolinas and my vision in an object to be shared with others . . . to be shared with others . . . to be able to focus on these poems and interact with a creative and collaborative project during the Covid pandemic. The months of grief mixed with the joy . . . pandemic, migrations, America’s failures within . . . what I heard predicted has come true, not in 100 years, but 20 years.”

Bolinas Frank: “The reader looks at the symbol, reads the poem, then through a brain wave interface converts the thought to a message sent to an artificial weather system device that can create, for example, a cloud right in front of them. The technology already exists today in brain interfaces for paralyzed patients and in those hyperlocal weather system sculptures.”

*

“I see devotion as an elevated state in a list of priorities,” Bolinas says. Bolinas is a Mishwa Native American word for the area of Bolinas, California, he says. “My parents told me that it means ‘Playground of the whales’ in Portuguese . . . I set my priorities based on ease of effort and importance. I see working with Mom very high priority with some effort. And creating art in general is the top priority which gives meaning to life.”

*

Forecast for tonight and tomorrow.

In the beginning, Day One, the Surface Map.

The first poem in Violent Rain, “Weather Station on Top of a Mountain.” (pg. 5, see poem below) Title, illustration, poem. The Poem:

Ants stream like red monks lining up

to collect sweet from whatever heat

rises and from everything tongue-pretty

with nectar in winter’s slip into warming.

This poem, a reviewer’s read. How’s your chastity coming along on this tongue-pretty summer evening, nectar-full monk? This abundant life overtaking your poverty. Your obedience is good. The good monk. But those red ants. And all your re-creational hiking. Weather poems in your head. And those ants.

*

Bolinas’ illustration. Black ink circle. Coming out from center bottom two identical black lines, at 45 degree angles. Like a road sign? Like stick legs? Not a cairn, trail marker. How weather? Reading the poems, studying the signs, look at the blown-up sign for Violent Rain on the cover, and turn to the poem entitled “Rain Violent” on page 71 (see poem below). The illustration will help you find and see all that’s inside Bolinas’ weather symbol. Attention to this will help readers read the signs.

Streaming ants disciplined. Weathered station. Hot. Focus, if you can, on the streaming ants, in their red-monk work. Their practice.

Ann: Spiers: “The symbols represent physical phenomena. [I often wonder if symbols (and myths/tales) gain power if a human directly encounters the experience and thus, in recall, the symbol increases in meaning and effect. A person is more affected if that person has encountered a bear, or Hansel and Gretel, or fire and ice.] In Rain Violent the symbols and their titles themselves were generated by individuals who experienced weather directly and wanted to record it. Over the years, they reached the collective agreement on the symbols, titles, and the description of the weather phenomena the symbols represent.”

Which came first: the weather, the signs, or the poems, I ask Bolinas. “The weather existed before life on Earth. So I’d say, the weather came first.”

*

Bolinas Frank: “In 1873, the International Meteorological Organization agreed on this set of symbols to replace the previously used alphabetic characters to represent the weather symbols and they have retained their characteristic of being heavily influenced by writing. I painted the symbol, took a photo, brought it into Adobe Illustrator, converted the digital image into a vector, then used font forging software to create the font file so that the printer can easily print the symbols in the way text characters are printed rather than printing an image, which is a block of pixels.”

*

“Thunder Heard” (see poem below) blows up in my face. The painting looking to me like a cattle brand. Poem and painting. Cliff wall or gallery? Cliff wall. It looks like the artist is having fun. But how does wolf survive? Los Lobos sing in my head. What about the poet? Snakes too starved to rattle. Our new cowboy boots.

Spiers responds, “Out of all the symbols, I like “Lightning, No Thunder” (page 34 see poem below). The arrow suggests so much: broken as in maimed, or bent as in changing one’s mind, bent as in not in good condition or bent into something negative or dancing, sorta Isadora Duncan. Other arrows attract me. “Snow Blowing” (arrow pointing in two directions = confused, lost in snow), “Ice Needles” (two sharp points = pain).

*

Poetry’s ancestry woven tightly into the 4-line quatrains.

*

Following the signs, reading. Rain—from slight to continuous, heavy and slight. One drop of ink. A triangle of three—ink spots? A field of four is heavy rain. Back to drizzle slight. Drizzle Slight’s sign, like punctuation, apostrophe or comma. Perhaps a dried flower head off the freeway. Teasel’s dried flower beauty tall beside railroad tracks. Placed in a vase.

*

Looking at each page, wondering, where wonder surfaces. What is the relationship between sign and poem? The book fits in one’s hand like a field guide. It has to be in your hands. How it moves us. Moving the book from hand to hand.

Bolinas Frank: “Both are representations, one being a word and the other being a picture. [I ask: Prophet or reporter?]: Mom can answer this. I don’t know if in 2020 we’d predict the spectacular weather tragedies that would happen this year in 2021. Twenty years ago, I wouldn’t call a weather symbol art. But today, weather has become inherently political. It demands our attention. And it’s sad that there is an argument that climate change is not real.”

*

News in the poems stays news. Westside Seattle rain, continuous, wearing gear, sometimes naked on bicycles. The focused poet-eye: shower caps, crinkling over coiled hair. Crinkled and coiled. Something going on. Weather changes in a moment. To drizzles, thick, to snow, freezing, granular. Not a children’s story. Dead and dying bumblebees, count them. Biblical, plague-like. Moses in Exodus. Truer than that one in the Bible. Polio-Palestine dust. Bolinas Frank’s brush line straight through a triangle of troubled weather.

Unsettling hailstorms. Bears walking into strip malls. Hail taking out the children. Dying Joshua trees, parched for the water-diversion program supplying the church car wash.

We’re all marginal now. Los marginados in Central America report on the mayor’s proclamation of water for all. Show us the faucets.

This weather. Flutter on the branch, evanescent birds, Emily Dickinson. Always rapid movements of the migrant worker’s quick hands. Dickinson’s evanescence. Branch moving. There was a bird here.

*

For the poem titled, “Weather Station on a Plain,” (pg. 23) Bolinas copies the symbol . . . a black circle resting on flat brush stroke. Spiers explains,

“This quatrain is a family memory, this idyll. A resting place”:

My Dad discovers gold in an aerosol can.

Like Midas, he gilds all. The ozone thins.

I ride my golden bike, my skin bronzing

under the sun’s ultraviolet rays.

The golden bough. Doug Fir cut into 2x4s, and spray paint. What Dad did for us. His simple wonder. That bicycle, and such skin! Here is the music. Woody Guthrie, Leonard Cohen. Wordsworth’s daffodils. Here, too, Gerard Manley Hopkins. Bright wings of birds at dusk.

Cut to the lightning, to thunder. This is worship. High drama. Tracking this weather. This absorption, packed into an hour. Thunder herd. Thunder heard. Anything but yourself is the herd. But, man! Thunder road and the wipers don’t work. The pumps don’t work. Bob’s Hard Rain always in our heads. Deep in the Rock, Tséyí Diné poet Laura Tohe’s Reflections on Canyon de Chelly, beautiful and remaindered book arrives in the mail before a trip to the SW. This male rain:

Laura Tohe’s poem, “Male Rain”:

He comes riding a dark horse: Angry. Malevolent. Cold.

Bringing floods and heavy winds.

*

Rain Violent. Spiers’ rain. It runs the gully. “. . . children learn / cut-and-pasting data.” That hard rain, Bob. Falling violent. What can’t be said, said. Violent rain.

Attentiveness and consciousness established in these quatrains, Ann Spiers. The poet shows once again how she walks. Vashon Island’s first inaugural poet laureate, Back Cut (Black Heron Press) and Harpoon (Ravenna Press, Triplet Series) are her two new volumes of poems also appearing in 2021, alongside Rain Violent. Her footprints, clean. Her way, on trails, in poems, garners and fosters. Name her, poet, considering this: she writes interpretive signage for natural history museums, land trusts, and parks. Her Vashon trail guide is a best seller.

*

This is a book of poems that fits into your hands. Small poems crafted.

Ann Spiers. Prophet and reporter. An elder poet now. It seems odd to say that, but I have had her White Trainbroadside hanging in my house since 1986. “The white cars / racketing past / bending migrants / paralyzed / over asparagus shoots.”

Spiers walking trails. Her practice over time. Touching earth and sky. Polarities and white space. There is no ego in the poems, not a smidgen of ‘look what I can do,’ Practice and how to practice. That sky overcast.

Bolinas credits a mentor on the Artist’s Page, from Seattle’s Fine Arts Center, where Samaj taught him to be fearless through the understanding and feel of materials. “Samaj blasted away all preconceived notions. We would take a break each session and go out into the park at 20th and Yesler to let out a cathartic yell to really loosen us up.”

Burroughs Mountain, misnamed Rainier. Where I hike with grandkids. Where I read these poems. The reclaiming of the mountain’s name is as central as the weather. The Puyallup Nation calls it Mount Tahoma. Mother of waters. That Place of Frozen Waters. Large Snowy Mountain. All of us under the sun, exposed.

Bolinas: “No cover from the sun.”

Howl.

Where the poet lives, this. A last word.

Ann Spiers: “An east wind, after gaining force descending the Cascade Mountain slope, arrives in a sheet of waves inundating the property. All in all, the best place to live so close to water and weather and learn how to start a fire, strike a match.”

Jim Bodeen writes with a given word, Storypath/Cuentocamino, and maintains a poetry blog, https://storypathcuentocamino.blogspot.com/. He began Blue Begonia Press in the early 70s, serving for 30 years as publisher, editor and printer. His work with young Chicanos/as and Mexican Nationals, resulted in two award-winning anthologies, changing his life direction. He has published several poetry collections and chapbooks from Tsunami and Empty Bowl. Currently he is part of the Yakima Immigration Response Network (YIRN), witnessing weekly deportation flights of asylum seekers from Tacoma Detention Center through Yakima to the southern border. YIRN has witnessed more than 125 flights, reporting to UW Center for Human Rights. He enjoys writing essays on poets whose poetry confronts and sustains our world.