Anna Bálint Reviews Wandering Star by J.M. G. Le Clézio

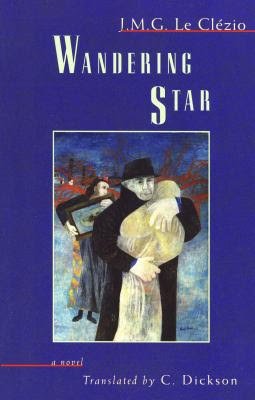

Wandering Star

by J.M. G. Le Clézio

A Review by Anna Bálint

Note: This review is reprinted from Raven Chronicles, A Journal of Art, Literature & The Spoken Word, Vol. 14, No. 2, Architecture in Literature, 2009. This book was originally published by Curbstone Press in 2004.

Set against the backdrop of WW2 and the founding of the state of Israel, Wandering Star is a remarkable novel. Written with deep compassion and in sumptuous language, it encompasses the stories and viewpoints of two adolescent girls: Esther, who is Jewish, and Nejma, who is Palestinian. It is also a story about the land, the earth on which we live, and the ways in which landscapes and the natural world are a part of human identity, both who we are and who we become. “Does the sun not shine for us all?” the novel asks.

None of this is presented simplistically. There are no neat parallel stories, no back and forth chapters, or a book divided into halves, one for Esther, the other for Nejma. A master storyteller, Le Clézio’s structure is both more subtle and complex than that, with Nejma’s story literally imbedded within Esther’s, breaking it open at a critical point, and ultimately changing it.

Esther is the wandering star of the title, and when the novel begins, in the summer of 1943, she is thirteen years old and living with her parents in a mountain village in the south of Nazi occupied France. While German troops have yet to march into Esther’s village, Italian troops are stationed there, and there are daily identity checks for Jews, many of whom are refugees from Poland, and other occupied countries. Yet despite a sense of growing danger and things brewing beneath the surface, there is also an almost dreamy quality to this early part of the novel, as if “…there had never been a summer before that one.” Surrounded by the beauty of the mountains with a river rushing down its slopes, Esther climbs and explores the hillsides, tries to make sense of the changing world, and her own adolescent longings. The third person narrative both shadows Esther, looking out at her world through her eyes, while also watching her scramble through the grass, so that at times she almost becomes a part of the landscape. This is omnipresent, and described in ways that are lush, and life affirming. “The sunlight, the sky in which all the clouds were just beginning to swell, and the vast grassy fields where the flies and bees hung suspended in the light, the somber walls of the mountains and the forests, all of that would go on and on.”

Here then, El Clézio gives us two stories of displacement, of war and exile, the one arising out of and contained by the other. In the end it is a single story.

But when German troops do arrive in the village, Esther’s life unravels, literally overnight. Her father disappears into the hills as part of the Resistance, and she and her mother flee into the mountains along with most of the local population of Jews. Even the peaks and clouds she so loves takes on an ominous cast during the long perilous trek. Life becomes one of hiding and hunger, and a longing for safety. By the war’s end, the world she once knew has vanished. There is no one to go back to, and so much to forget. Across the water the promise of Israel, of a new beginning in a Jewish state shines, like a beacon of hope.

Le Clézio switches back and forth from third to first person and back again several times during this novel, allowing the reader to sometimes times pull back a little ways from his main characters—though never far—and at other times closing the gap altogether, and taking us right inside their heads and inner lives, to look out at the world through their eyes. This latter is done to great effect as Esther prepares to embark on her journey to Israel, and we are privy to the inner turmoil she experiences as she huddles with other Jewish refugees on a cold beach “like animals gone astray in a tempest.” The journey involves hiding in the hulls of boats, capture, imprisonment, and having to wait and hope all over again. “How many doors will we go through?” she asks. “Each time we crest the horizon, it will be like another door.”

Through all of this, the natural world and rawness of the elements to which Esther is exposed literally bombard us with contradictory images. “The sea is a blinding blue” and “painful to look at.” The sun burns, the wind whips, the sea churns. And yet, “the sea is so beautiful with its slow swell coming from the other side of the world.” In this way, Le Clézio creates a powerful mood of both Esther’s anticipation and anxiety. He returns again and again to important moments in Esther’s life, replaying them as she replays them inside her head, though never in ways that halts the story. The city of Jerusalem takes on mythical proportions. “To keep from losing hope, to resist the cold wind, the weariness, we must think about the city that is like a mirage, the city of minarets and domes shining in the sun, the dream city made out of stone hovering over the desert. In that city we can surely forget.”

But Esther, barely arrived in the newly declared state of Israel, is on the road to Jerusalem, when into strange arid landscape appears a straggle of refugees. They are Arabs, displaced Palestinians. One of them is Nejma. And there on the dusty road a brief but unforgettable encounter takes place between the two young women. Almost immediately the entire trajectory of the novel shifts, and becomes Nejma’s story.

Now it is Nejma who speaks to us, directly, poignantly, from her vantage point of life in a refugee camp. “… Every morning the sun would rise over a land that gradually grew more bitter, red, scorched, with wispy thorn bushes and those acacias incapable of providing shade…” Here Le Clézio’s repeated images of dust, hard earth, and unrelenting heat create a sense of alienation; of a place that is completely inhospitable. “The Nous Chams Camp is undoubtedly at the very end of the world,” Nejma tells us. “Because it seems to me that beyond this point there can be nothing else, there is no hope left.” The camp itself is made up of endless rows of “houses of planks and cardboard” “torn tents” and “makeshift shelters.”

Nejma’s story picks its way through this landscape as all around her things deteriorate further and further, where “little by little, even the children stopped running and shouting and fighting around the camp. Now they stayed near the shacks, sitting listlessly in the shade on the dusty ground, half-starved and looking like dogs, shifting positions according to the movement of the sun.” In contrast to this sparseness, and the sense of nothing much happening, there is the ever-present ache in Nejma’s heart, which is immense. Like Esther, she has been completely uprooted from the life she once knew. “We’ve been prisoners in this camp for such a long time. It’s difficult for me to recall what it was like before, in Akka. The sea, the smell of the sea, the cry of the gulls. The fishing boats slipping across the bay at dawn. The call to prayer at dusk, in the twilight, as I walked through the olive groves by the ramparts. Birds flew up, last turtle doves, silver winged pigeons suddenly crossing the sky … I’ve lost all of that now.”

Eventually Le Clézio returns us to Esther’s life and narrative, except it is now haunted by Nejma, both for the reader and for Esther herself. Years pass. Esther’s life in Israel, a country often at war, is not easy. The direction of her life was forever altered by WW2 and the holocaust, and continues to be shaped by war. In a sense she never stops wandering, and there is much she can never forget, including Nejma, “my sister” who sometimes comes to Esther in dreams, “from exile, from forgotten drought ridden lands, alone, to observe me.”

Here then, El Clézio gives us two stories of displacement, of war and exile, the one arising out of and contained by the other. In the end it is a single story. By beautifully mirroring the complexity of history Wandering Star rises above politics, religion, and culture to speak to our common humanity. In so doing, it also sheds light on one of the most burning issues of our day: the Israeli/Palestinian conflict.

Anna Bálint is a London-born, Seattle-based poet, writer, editor and teacher of East European descent. Her most recent editorial work is the anthology Take a Stand, Art Against Hate (Raven Chronicles Press, 2020). Her story collection Horse Thief (Curbstone Press, 2004), was a finalist for the Pacific Northwest Book Award, and her poems, stories, and essays have appeared in numerous journals and magazines. Two earlier books of poetry were Out of the Box and spread them crimson sleeves like wings. An alumna of Hedgebrook’s Writers in Residence Program and the Jack Straw Writers Program, Anna has also taught creative writing for many years and in many places, including Washington State Prisons, El Centro de la Raza, Writers in the Schools, Antioch University, Richard Hugo House, and Path with Art (all in Seattle). In 2001, she received a Leading Voice Award in recognition of her creative work with urban and immigrant youth at El Centro de la Raza. Currently she is a teaching artist at Recovery Café where, in 2012, she founded Safe Place Writing Circle for people in recovery from trauma, addiction, mental illness, and homelessness.

Wandering Star

J.M. G. Le Clézio,

Translated by C. Dickenson

Northwestern University Press

https://nupress.northwestern.edu/9781931896566/wandering-star/

2009, paperback, 328 pages, 5.50x8.50 inches, $17.95